The Chicago School emerged at a time when sociology was beginning to establish itself as a scientific discipline. In the early 20th century, scholars from the University of Chicago, such as Clifford Shaw and Henry McKay, initiated an ambitious project to understand the social dynamics underlying criminal patterns in the city. Their approach, radically innovative for the time, posited that crime was not randomly distributed across urban space, but rather followed patterns that could be explained by the social and economic conditions of different city areas.

Fundamental Principles of the Theory

The theory of criminal ecology or social disorganization is based on the idea that urban areas undergo constant processes of change that affect the social structure of their communities. Shaw and McKay identified that areas with high crime rates often featured difficult living conditions, including poverty, high population density, and a heterogeneous mix of residents. They argued that these conditions led to a decline in both formal and informal social control, creating an environment conducive to the development of crime.

Social Surveys and Biographical Analysis

One of the most significant contributions of the Chicago School was its methodological approach. Researchers employed detailed social surveys and biographical analyses to gather data on individuals’ lives and their environments. This approach allowed for a deep and multifaceted analysis of crime, considering both structural and personal factors. The surveys aimed not only to collect basic demographic data but also to understand the social, economic, and cultural relationships influencing criminal behavior.

Crime Mapping

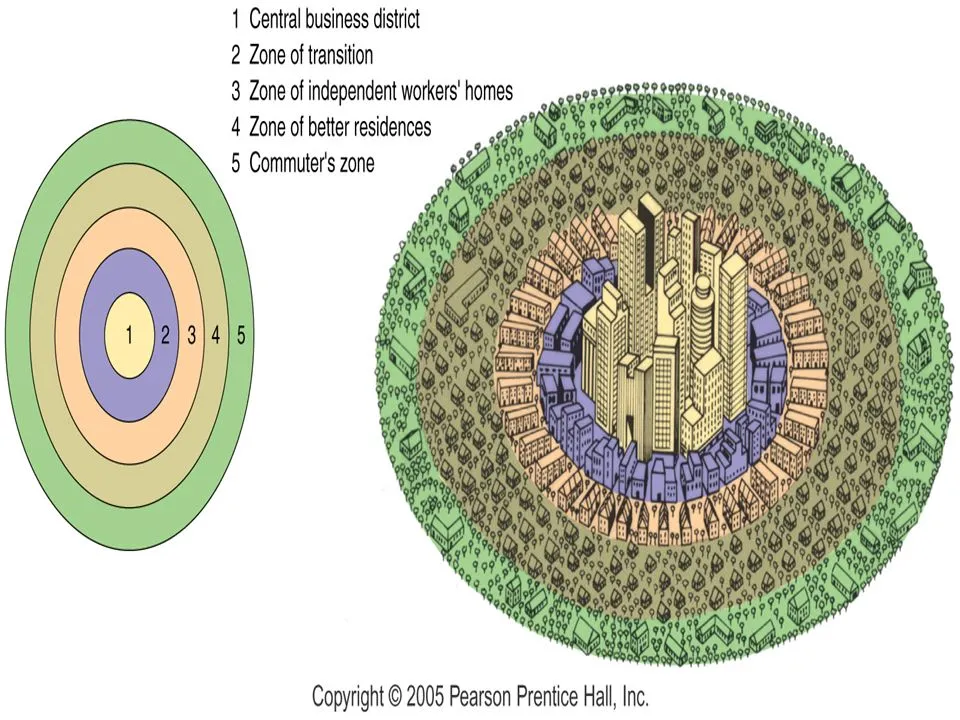

Another pioneering methodology was crime mapping in the city. Shaw and McKay developed detailed maps showing the distribution of criminal activities in Chicago, identifying areas with particularly high concentrations of crime. This approach allowed for visualizing the relationship between urban space and crime, and served as a basis for identifying “transition zones”—areas experiencing high levels of social disorganization and, therefore, elevated crime rates.

Adaptation and Social Consequences

The Chicago School also explored how individuals and communities adapted to urban conditions. They recognized that, despite general trends, there were significant variations in how different groups responded to their environment. This observation underscored the importance of considering individual agency and community support networks in crime analysis.

Implications and Legacy

The ecological theory of crime and the methodologies of the Chicago School have had a lasting impact on criminology and urban sociology. Their emphasis on the importance of social and economic context in the generation of crime has informed numerous public policies and urban intervention strategies. Moreover, their investigative techniques, especially the use of crime mapping and biographical analysis, continue to be fundamental tools in contemporary crime studies.

The work of the Chicago School marked a turning point, demonstrating that crime is a complex phenomenon influenced by a mixture of social, economic, and environmental factors. Its legacy endures in the ongoing exploration of how our cities and communities can be designed and managed to promote safer and more cohesive environments.

Applying Ecological Theory to Contemporary Urban Challenges

Exploring how the Chicago School’s theories apply to contemporary urban challenges offers us an opportunity to understand the enduring relevance of these concepts in the analysis and mitigation of crime in modern cities. The theory of criminal ecology and social disorganization proposed by Clifford Shaw and Henry McKay provides a framework for examining the complex interactions between urban structure, social inequality, and crime. In the current context, these principles are used to address various urban challenges, including planning safer cities, developing inclusive public policies, and implementing community-based crime prevention programs.

Urban Planning and Environmental Design

The influence of urban structure on criminal behavior has led urban planners and environmental designers to carefully consider how the design of urban spaces can contribute to crime prevention. Principles such as natural surveillance, controlled access, and maintenance and activity in space, derived from the theory of Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED), reflect the contemporary application of ideas on social disorganization and informal control. Creating well-lit public spaces, safe parks, and streets that encourage social interaction can help strengthen community cohesion and reduce opportunities for crime.

Inclusive Public Policies

Identifying “transition zones” with high social disorganization and elevated crime rates underscores the need for public policies that address the roots of inequality. Initiatives aiming to improve education, access to employment, affordable housing, and mental health services in these areas can mitigate the factors contributing to crime. These policies reflect a more holistic and preventive approach, focused on strengthening the social and economic fabrics of vulnerable communities.

Community-Based Crime Prevention Programs

The concept of informal control is particularly relevant for developing crime prevention programs that mobilize community resources. Initiatives like neighborhood watch, conflict mediation programs, and youth empowerment activities can foster a sense of shared responsibility for safety and well-being in the neighborhood. By promoting active participation of residents in the surveillance and maintenance of their environment, these strategies seek to rebuild the informal social control that the ecological theory identifies as essential for crime prevention.

Final Thoughts

The application of the Chicago School’s theories to contemporary urban challenges demonstrates that, although the social and technological context has changed significantly since the early 20th century, the fundamental principles of criminal ecology remain relevant. Understanding crime as a problem rooted in the social and spatial structure of cities compels us to consider solutions that address both the symptoms and underlying causes of social disorganization. By doing so, we can advance toward creating safer, more inclusive, and resilient urban environments.